‘Life Here is Death’: Waiting for Help That May Never Come in South Sudan

October 11, 2018 05:30 AM

BY MELINDA HENNEBERGER

NZARA, SOUTH SUDAN — The baby is skeletal from malnutrition, and so dehydrated that her skin is as thin and wrinkled as if she’d survived a century. Instead, these are almost certainly 20-month-old Josephine Moses’ last hours, though the mother who took her into the bush to protect her from this pointless war, but then watched her shrivel away there, is still trying to get her to take her breast. “That’s her crying,” whispers one of the nurses here at St. Therese Hospital, where Italian nunsbegan treating leprosy and TB 64 years ago. The little girl’s mouth is open wide, but if she’s screaming, we can’t hear anything, as in a nightmare. She’s too weak to make a sound.

Baby Josephine’s whole country is like that — young, devastatedand so hard to look at in this condition that we’d really rather not. Even including the words “South Sudan” in the headline means few readers will have made it this far into a story about a countrywe’ve actually invested a lot in, and not only financially. In fact, it’s no exaggeration to say that the U.S. helped bring South Sudan into being in 2011. And then, when the abused became the abusers, maybe because the fighters in charge knew nothing but violence after 30 years of war with their Sudanese oppressors, webacked away from this new democracy, not at all without reason.

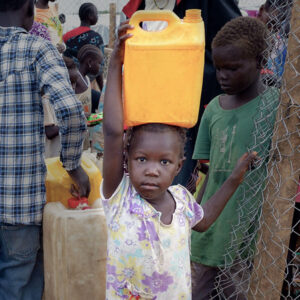

Millions of civilians — about a third of the country’s population — have been driven from their homes in the five years since their feuding officials drew their respective Dinka and Nuer tribes into a conflict in which children have routinely been kidnapped and then forced to fight, and gang rape is as standard-issue a weapon as an AK-47.

There are more than 60 other tribes in the country, too, and dozens of opposition groups. But if there’s one thing the South Sudanese agree on, it’s that their latest peace agreement, signed just last month, was violated within hours. The international community, which isn’t nearly as bloodless as that name tag makes them sound, does view this treaty as yet another bald bid for aid they’d only steal from their own people. Maybe that’s because they’ve given President Salva Kiir and his once and perhaps future vice president, Riek Machar, the benefit of the doubt before.

With an estimated 380,000 people killed in this conflict, in a country of 12 million, most families have lost loved ones, and virtually no one who’s survived them has a lot of faith in this particular piece of paper. Even the wild animals, who are said to sense both war and peace before humans do, haven’t come back out of hiding. And the people living in refugee camps or seeking sanctuary in churchyards where they sleep on mats under mango trees have not headed home yet either. Ask them, and they’ll tell you they aren’t even thinking of risking it. But are we as willing to let them die where they are as their so-called leaders are?

Some 70,000 farmers forced out of their villages have relocated to a forest in Mabia, outside Tambura, where they live in a fog from lack of food, with no protection from even the rain. In May, they ran first from the rebels and then from the government troops who came chasing after them, killing everyone and even burning alive the elderly and disabled who couldn’t flee, in case they were rebels, too. In August, those who survived the trip arrived here empty-handed and starving, having buried many of their children along the way.

The kids who made it this far all seem to have fevers and diarrhea, and their hunger is terrible, even with various aid outfits helping, because supplies just don’t stretch far enough. I ask several people what they’ve had to eat in the last 24 hours, to get an idea of the gaps, before realizing why they look away without answering. They’re too embarrassed to say what 44-year-old Magdalena Gima finally does: “I haven’t had anything to eat today.” And yesterday? “Some cassava leaves.”

Woman after woman tells me, in the affectless monotone of the most seriously wounded, about losing children on the way here — as in, they ran in different directions when the bullets flew and haven’t been heard from since. No one has any means of communication, or electrical power, so even if their lost children were alive somewhere, contacting them would be impossible.

Now, as they wait for the help that they’re not sure is coming, the almost entirely Catholic population in this part of the country really only trusts in their church. Unlike in the U.S. (and Ireland,Germany, the Netherlands and Australia, to name just a few other scandal hotspots), the Catholic Church in many ways is civic society here, and the only institution with any moral standing.

The local bishop, Eduardo Hiiboro Kussala, who was born not far from here, and stops to greet some cousins on the road, himself grew up in a refugee camp in Congo. He doesn’t live much differently than his flock does, and the people living in the forest who run to ask him to bless their rosaries seem to crave the little bit of hope he’s trying to give them as much as anything else they’re lacking.

He can speak to them in a way others can’t, because somehow, he made it out of a place just like this. He’s also managed to negotiate safe spaces for civilians in churchyards across his country. Though he never mentions it, he has been heavily involved in peacemaking efforts, and risked his life going into the bush to persuade various opposition groups to lay down their arms.

Maybe there were easier ways to remember why I’d want anything more to do with the Catholic Church, after all of the damage done by clerical abusers and their protectors. But here in the world’s most dangerous country for aid workers — yes, even beyond Afghanistan and Syria — I did find a church doing everything its founder ever asked of us.

In St. Therese Hospital in Nzara, I found the Italian nun who runs the place essentially willing a new maternity ward into existence, brick by brick. If the ceasefire ever holds, Sister Laura Gemignanisays, she could export enough coffee and vanilla to pay a few more doctors to join the only one who’s here now. Meanwhile, both of them work 13-hour days.

Baby Josephine did die, of renal and lung failure caused by severe malnutrition, two days after my visit. She was the third infant that week to starve to death in that one hospital, in a place where the land is so lush that malnutrition was unheard of before the war. The serious diseases Laura’s team is up against include an out-of-control resurgence of AIDS, fueled by maddening rumors that they know how to cure HIV over at St. Therese’s, so why take your medicine? Yet half of the 123 people who died here in the last year were malnourished babies.

On a dirt road past several teak plantations, over in Riimenze,east of Nzara, almost 8,000 people have taken sanctuary in a Catholic churchyard, and their number is still growing. The nuns and priests there teach carpentry, run a farm and nurse the injured antelope people bring to them. With support from theCatholic Medical Mission Board, Solidarity with South Sudan and the Sudan Relief Fund, with whom I’m traveling, they are able to offer some basic health care and give every child a bowl of porridge every day. On Fridays, everyone gets a serving of beans, and the elderly get mosquito nets and rations once a month.

But these people who were once fully self-sufficient, and even sold their surplus, still have to forage for food and firewood. The rest of their days are passed in endless games of a variation on backgammon played with acorns or rocks. Sometimes, they sneak back to what’s left of their nearby homes and try to cultivate their own land, though they know this isn’t safe.

There are signs of normal life here, like little girls walking through the camp holding hands, and older ones braiding one another’s hair. Yet nothing about this is either normal, or life as they’ve known it.

Just that morning, a man had ridden up to the camp on a bicycle, sweating and pumping and yelling that a dozen rebels with RPGs had been seen crossing the road near the village of Bodo, about 6 miles away.

The government troops stationed nearby have even less to do than those in the churchyard, and sleep outside with their guns next to them in the heat of the day. So they come over to see what I’m up to. “Whenever you come without telling us, we become very unsettled,” says Major Juma Tong, who has a bodyguard with him.

He warns me about the rebels, too, though what he really wants is a few dollars of “tribute.” With no vehicles that are any good on these deeply rutted, practically nonexistent dirt roads — the only paved ones in the country are in the capital — he couldn’t chase any rebels if he wanted to.

Maybe you’re wondering where all those who weren’t safe even on church property or hiding in the bush have gone? They and all of their their losses and nightmares and painful memories are not so far away, in refugee camps in neighboring countries.

“I’m scared of South Sudan, after everything I’ve heard in the camp,” says a nurse who works in the largest of these, Bidi Bidi, just across the border in Uganda. An Irish missionary, Noeleen Loughran, isn’t scared of much. Five years ago, she sold everything and moved to Kenya to work in an AIDS orphanage. At Bidi Bidi, where for the last year she’s been living without running water, “You’d be crying every day, some of the things they ask you for are so mere, and back home, people are throwing things away, and Christmas starts in September.”

The disconnect between life here and the European-donated clothes that so many of the refugees are wearing — somebody’s once-fancy party dress or suit jacket back in Vienna or Paris — is so jarring that maybe you would be crying every day.

“Life here is death,” says 34-year-old Monday James. Most of the women and some of the men, too, have been raped repeatedly during the war. “Rape is almost a part of life for them, and the soldiers all have HIV, so rape is a death sentence,” Noeleen says, in a place where there aren’t nearly enough antiretrovirals.

No more South Sudanese are arriving here now, but not many are leaving, either, because “the same day we heard the news of the peace, we heard more were slaughtered and burned inside their houses,” according to Sitima Grace, who is 34.

The five men from Bidi Bidi who did go back to see for themselves were all killed on sight at the border as suspected rebels, these refugees tell me. So nobody else is in any hurry to follow, even if schools are so overcrowded that there are as many “learning through the window” from outside as there are inside.

On the day I spend with Noeleen, she treats hundreds of people — with ringworm, elephantiasis, cerebral meningitis, infections of all kinds and malaria, which she herself now has again. But the hardest for her to know what to do about are the effects of the trauma that nearly every person living here has suffered. That’s why 65-year-old Christina Anite, whose three brothers were all murdered, hears heavy waves crashing on some unseen shore. “It’s like the wind is blowing, even at night, and I start crying.”

There is no real psychiatric care, and Anthony Lupai, a 65-year-old farmer and carpenter with a blue rosary around his neck, is right when he says that people can’t live like this indefinitely: “If the seeds are all thrown in the same place, do you think the seeds can survive?”

In some ways, the peace treaty has only made life worse in the refugee camps because local Ugandans who’ve heard it’s been signed have started attacking women going out to look for firewood, and yelling at them that they can go home now. “Now I’m too afraid to go,” says Didmita Saima, a former government worker who is 45.

Tribal tensions inside the camp, which weren’t all left back in South Sudan, have flared recently, too. This summer, a squabble over a Dinka who sat in a Nuer’s chair when he left it for a minute while listening to the World Cup ended in the death of five people.

There are a some signs of peace in South Sudan, where’s it’s relatively quiet now. There are people on the road to Yambio at 5 in the afternoon, which is a change for the better, and one gas station has reopened, though no banks have. In Nzara, a few couples married recently, which never happened when such gatherings were sure to be attacked, and the local disco is back in business. “Even when we can’t sleep, it’s a good sign,” says Sister Laura.

But her hospital is still treating some gunshot wounds from the war, and on one recent afternoon, members of the majority Dinka tribe were running their cattle through the middle of Yambio, where a naked man with sleeping sickness stood in the center of the mud street. They do that to assert dominance, a local priest tells me, by showing that their long-horned bulls can walk over anything, anywhere, at any time. Usually, those displays mean another attack is coming.

In the capital city of Juba, where even the families of the local diplomats live outside the country for security’s sake, one member of the South Sudanese government, Joseph Akol Makeer, one of the former “lost boys of Sudan” who lived in Fargo, North Dakota, for years, tells me that he knows the United States is the truest friend his country ever had. With both Sudan to the north and Uganda to the south greedy for South Sudan’s oil, there isn’t a lot of competition for that distinction.

The way Joseph sees it, former President Barack Obama and his crew only lectured South Sudan, while President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo couldn’t find it on a map. Trump “needs to come to us,” he says, and treat President Kiir “like a younger brother.”

Given Trump’s views on aid, diplomacy and “s—hole countries,” that seems unlikely. But then, so was his professed love affair with the North Korean leader who makes Kiir look like a Cub Scout.

What South Sudan needs most desperately are leaders capable of delivering basic services, cracking down on corruption, checking the power of warlords and generally trying a lot harder to prove the world wrong.

With peace so elusive and so yearned for, is there anything we can do? Humanitarian aid really is what’s keeping them alive. And though it seems what Noeleen would call so mere, the South Sudanese people really do want to know that we haven’t forgotten them or their brutal, beautiful country, where everything grows and nothing works.