SRF 2015 3RD Quarter Newsletter

2015Q3NWLRFinalDocs

By William Davison

The European Union’s top envoy in the Horn of Africa urged South Sudan’s warring parties to implement a security deal to enable humanitarian agencies to provide aid to more than 1 million people facing famine.

A deal agreed on Aug. 25 is “critical” to stabilizing the country eight months after fighting began, Alexander Rondos said in a phone interview yesterday from the Kenyan capital, Nairobi. The accord sets out measures government and rebel forces should take, including disengaging from combat areas and reporting troop positions to regional monitors, and is a step toward respecting a cease-fire agreed in January that has been repeatedly flouted.

“It’s action on the ground on the security front that has to occur,” Rondos said. “With this we need to see immediate implementation and this is entirely in the hands of the South Sudanese parties.”

Fighting erupted in South Sudan in December when President Salva Kiir accused his former vice president, Riek Machar, and other senior government officials of plotting a coup, a charge they deny. The conflict in the oil-producing nation forced at least 1.5 million people to flee their homes and left the country on the brink of famine that may kill 50,000 children, according to the United Nations.

About 102,000 displaced people are sheltering at 10 UN bases, the highest number since the conflict began, according to the world body.

The mandate of a 12,500-strong UN mission may have to be strengthened to allow peace-keepers to push back armed groups threatening to attack, Rondos, the E.U.’s special representative to the Horn of Africa, said. The operation’s role was shifted in May from nation building to protecting civilians and a Protection Force of East African troops was announced in March.

“We need to see whether under present circumstances the mandate and rules of engagement they have at their disposal are equal to the challenge,” he said. “There’s going to be have to be strengthening of the enforcement capacity if it’s clear that persuasion has to give way to enforcement.”

Conflict mediators from the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, a seven-nation East African bloc, said they expect the step-by-step plan to mean “the guns will be silenced and the senseless conflict in South Sudan will end,” according to an Aug. 27 statement. Truce violations will be published on IGAD’s website, they said.

The number of South Sudanese refugees in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda and Sudan may double to more than 1 million people by the end of the year, adding to an already large burden for neighboring countries, Rondos said.

“If we can’t get separation of forces, you can not get access, supplies to the vulnerable populations,” he said. “If you can’t get supplies to them they will come to the neighbors.”

Bloomberg

August 29, 2014

By NICHOLAS BARIYO

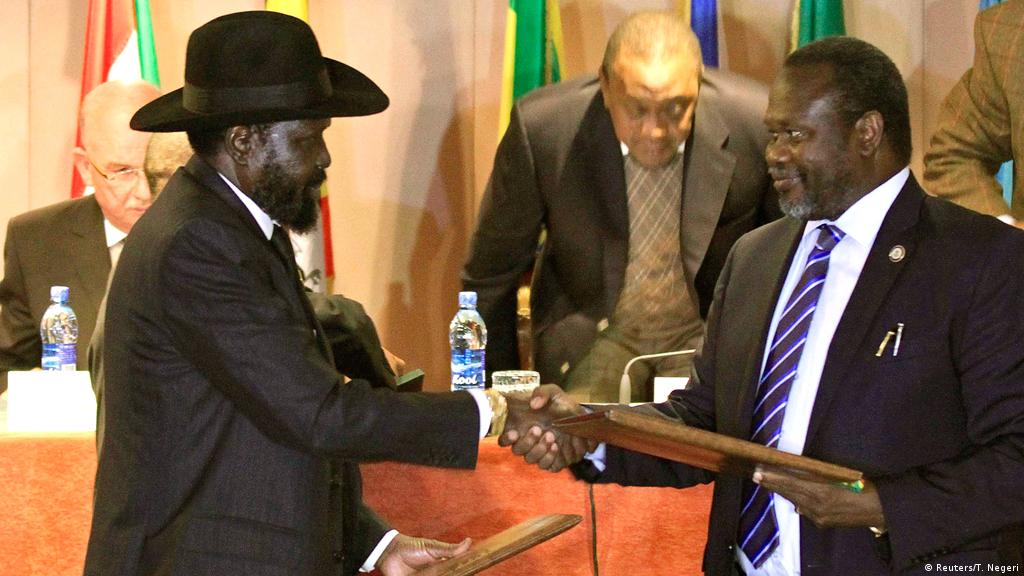

South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and rebel leader Riek Machar agreed to form a transitional government in the next 60 days, a big step in efforts to resolve a devastating six-month conflict in the world’s youngest nation, mediators said on Wednesday.

Government and rebel negotiators are slated to start talks on the formation of a transitional government of national unity on Thursday in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, according to a communiqué issued by the heads of state from East Africa’s regional trade bloc, the Intergovernmental Agency for Development, or IGAD.

The warring parties have 60 days to complete the talks and are also required to cease all military operations during the negotiations—or face punitive sanctions.

For the first time since the conflict erupted in December, IGAD leaders threatened late Tuesday night to impose sanctions on both parties.

The threat of sanctions, which diplomats said could include asset freezes and travel bans, came at an emergency summit in Addis Ababa and underscores the region’s growing frustration with South Sudan’s warring parties, which have violated previous cease-fire deals.

Although South Sudan’s political rivals have committed to the 60-day road map, those close to the conflict remain skeptical another promised cease-fire can hold.

“The leaders need to act swiftly on their promises by calling on their troops to lay down their arms immediately,” said Oxfam’s South Sudan country director, Cecilia Millan. “The people of this country have been forced to endure too much in the past six months.”

The conflict has also drawn in Uganda, and diplomats have singled out the presence of Ugandan troops as an impediment to peace.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, who deployed troops to support a government offensive against rebel fighters shortly after the outbreak of the conflict, attended direct talks between the warring factions, the Ugandan presidency said.

James Gatdet Dak, a rebel spokesman, described Mr. Museveni’s participation as “a very good sign” for the peace process. It signals, he said, that interested parties “will now address the root causes of the crisis.”

But even as IGAD heads of state discussed the conflict, the United Nations mission in South Sudan said heavy gunfire and mortar shelling rocked Malakal, the capital of oil-producing Upper Nile state. The U.N. accused government officials of using a radio station in the oil hub of Bentiu to deliver threatening messages to civilians.

South Sudan’s military said it was investigating the allegations.

South Sudan’s oil regions have seen some of the heaviest combat since the conflict erupted and crude production has since dropped more than 30%, to 160,000 barrels a day, a severe blow to the country’s economy.

Messrs. Kiir and Machar agreed to form a transitional government in May, in a U.S. brokered deal, where they also signed a second cease-fire deal, after the previous one failed to hold. Sporadic fightinghas since continued, raising fears among aid officials that the ethnically charged conflict, in which more than 10,000 have been killed, could escalate into genocide.

Messrs. Kiir and Machar attended the IGAD summit and held face-to-face talks for the second time since the conflict erupted.

They agreed to recommit to the two previous cease-fire deals and allow unhindered humanitarian access to more than one million people who have been displaced.

In May, the U.S. Treasury Department ordered asset freezes and travel bans on Peter Gadet, a rebel commander loyal to Mr. Machar, and Gen. Marial Chanuong, head of Mr. Kiir’s presidential guards, for their role in the conflict.

The U.S. accuses Gen. Chanuong of ordering attacks against civilians in and around Juba shortly after the outbreak of the fighting. Mr. Gadet is accused of leading rebel forces during an assault on the oil hub of Bentiu in April that killed more than 200 civilians.

The Wall Street Journal

June 12, 2014

pg. A9

http://online.wsj.com/articles/south-sudan-peace-talks-reach-apparent-breakthrough-1402473616#

NAIROBI, Kenya — Horrific, ethnically motivated attacks of physical and sexual violence launched in South Sudan by warring parties constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity, Amnesty International said Thursday, while a new U.N. report said more than 300 people men from one ethnic group were slaughtered in one incident.

U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said during a visit to South Sudan this week that the country has seen serious human rights violations. The U.N. report said that gross violations of human rights and international humanitarian law have been committed.

Much of the violence has been ethnic in nature and carried out by troops loyal to President Salva Kiir, an ethnic Dinka, and rebels loyal to former Vice President Riek Machar, an ethnic Nuer. The two men are scheduled to meet for face-to-face talks in Ethiopia on Friday. If the meeting happens, it would represent the biggest breakthrough since fighting broke out in December.

Thousands of people have been killed and 1.3 million have fled their homes. Ban had been pressing for a monthlong cease-fire beginning Wednesday so that residents could return home and plant crops, but South Sudan’s military spokesman, Col. Philip Aguer, said Thursday that he had no information on a cease-fire being ordered.

Aid groups fear that if residents don’t plant crops this month, the country could face mass hunger or famine.

The U.N. report documents the killings of “at least 300 Nuer men” in a neighborhood of the capital, Juba, the day after the violence broke out. The report said that bodies from many attacks were taken to unknown disposal sites.

Nuers across Juba were targeted by armed attackers wearing military and police uniforms, the U.N. report said.

The U.N. representative in South Sudan, Hilde F. Johnson, said accountability for the crimes is critical to ending the legacy of impunity in South Sudan and preventing similar atrocities in the future.

The Amnesty report documents the rapes of children and the shooting deaths of the elderly while lying in hospital beds. In one horrific act of violence, the report documents the rape of a 10-year-old girl by 10 men.

“Forces on both sides have shown total disregard for the most fundamental principles of international human rights and humanitarian law. Those up and down the chain of command on both sides of the conflict who are responsible for perpetrating, ordering or acquiescing to such grave abuses, some which constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity, must be held accountable,” said Michelle Kagari, Amnesty’s deputy director for Africa.

Associated Press reporters saw the aftermath of South Sudan’s violence in the contested city of Malakal in December and February in which dozens of houses were burned to the ground, patients were shot while lying in hospital beds, and corpses littered the streets.

The Amnesty report documents how the bodies of 18 women were found outside St. Andrew’s Catholic Cathedral in the town of Bor in January. Six of the women were members of the clergy, the report said. All were ethnic Dinka.

A woman told Amnesty that her 20-year-old son was taken from her home in Juba, tied up and shot. She said she then fled to a neighbor’s house where she and nine other women were gang raped by soldiers.

By Associated Press

Published: May 8, 2014

http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/gross-human-rights-abuses-seen-in-s-sudan-report/2014/05/08/69efbe4a-d696-11e3-8f7d-7786660fff7c_story.html

Some 3.5 million South Sudanese, or one in three people, face an acute lack of food, the United Nations says. A widespread famine is looming after violence disrupted farming and food prices soar. In Sudan, food is scarce in Darfur, the Nuba Mountains and some eastern parts. But with fertile soil and water access, both Sudans are potential bread baskets. The Niles correspondents from across the region spoke to farmers, firms, governments, NGOs and the people about the crisis and the future.

By Nicholas Bariyo

KAMPALA, Uganda—The World Food Program has started emergency airdrops of food to millions of people isolated by conflict and rainy conditions in South Sudan, the food agency said Monday, in the latest effort to address an unfolding crisis in the world’s youngest nation.

The World Food Program is conducting the daily drops out of bases in South Sudan, Uganda and Ethiopia to provide food and nutrition assistance to at least 2.9 million people in the three oil-rich states of Upper Nile, Unity and Jonglei by the end of the year, said Lydia Wamala, the spokeswoman for the WFP in Uganda.

The process is expected to continue over the next two months but could last longer as a civil war continues to ravage South Sudan, Ms. Wamala said. The current conflict, which began in December, has splintered the country along ethnic lines, pitting President Salva Kiir’s Dinka community against former vice president Riek Machar’s Nuer tribesmen.

Insecurity and inadequate infrastructure in South Sudan have compelled the food agency to use the airspace of Uganda and Ethiopia to reach people in dire need of food, officials said.

“WFP is using land, air and water to deliver food to people who are isolated by conflict and facing intense hunger,” said Alice-Martin Daihirou, the organization’s country director. “While WFP’s team here in Uganda is providing this critical logistical support to our colleagues in South Sudan, we are also assisting a growing number of South Sudanese refugees.”

The development comes a few days after WFP said that more than 150 of its trucks carrying food aid for displaced people had become bogged down after heavy rains collapsed bridges and covered roads with mud.

More than 10,000 people have been killed in the conflict and up to 1.5 million remain displaced. The warring factions have signed two cease-fire deals since January, but there has been little to show for months of talks. East African mediators had set a deadline for Messrs. Kiir and Machar to form an interim government, but they failed to do so in the allotted time.

Diplomats say both sides continue to violate the latest truce as halfhearted negotiations continue in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa.

The conflict has disrupted farming and harvests over the past eight months, exacerbating the country’s food crisis. With only 4.5% of South Sudan’s land under cultivation, the government has always depended on oil revenues to meet food needs, but oil regions continue to be the scene of the heaviest combat. Crude output has dropped by a third to 160,000 barrels a day, a severe blow to government revenues.

The country broke away from Sudan in 2011, taking with it nearly 75% of Sudanese oil fields, but remains among the least developed nations in the world with virtually no basic infrastructure such as roads and railways.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture organization, food reserves are completely exhausted in areas isolated by the conflict, putting some 3.5 million people at risk of starvation. As the conflict continues, aid officials have warned that South Sudan is headed for the worst famine since the 1980s, when the U.N. has estimated that more than a million people died in the Horn of Africa.

http://online.wsj.com/articles/food-airdrops-aim-to-relieve-suffering-in-south-sudan-1410172436

Wall Street Journal

September 8, 2014

On 24 September 2014 I presented and offered preliminary analysis of a document I had received on 22 September 2014, from a source within Sudan whom I trust implicitly. It was an explosive document, containing the “Minutes of the Military and Security Committee Meeting held in the National Defense College [Khartoum]“; the meeting referred to took place on August 31, 2014; the date of the minutes for the document is September 1, 2014 (Sunday).

What makes the document so extraordinary is the participation of the regime’s most senior military and security officials, expressing themselves freely, and in the process disclosing numerous highly consequential policy decisions, internal and external. I discussed at some length issues of authenticity, and concluded the evidence was simply overwhelming that this was an authentic document, recording the words of men of immense power speaking without restraint about their goals, their fears, their policies. Subsequently I have received a good deal of additional evidence of the authenticity of the document, with no meaningful or substantial challenge offered to my assertion of that authenticity.

The words I am reporting are indeed the words of the men who control power, especially military and security power in Sudan, and have overseen 25 years of savage, self-enriching tyranny. The 30 pages of minutes are dense with revelations—some small, some large, some not so much revelations as shocking confirmation of what has been evident but never publicly confirmed by the National Congress Party/National Islamic Front regime.

In attendance were fourteen of the very most powerful men in the increasingly militarized regime (only two were not senior military officers). These included First Lt. General and Vice President Bakri Hassan Saleh, who will become the most powerful man within the regime if President (and Field Marshal) Omar al-Bashir dies from his health problems, or is medically unable to run again for president in the elections of 2015.

The Strategic Decision to Support Rebels in South Sudan

The minutes of the 31 August 2014 high-level meeting return on a number of occasions to South Sudan and, in particular, the role Khartoum intends to play in determining the outcome of the conflict. The concerns are final a determination of the North/South border (still not delineated, let alone demarcated, with key areas in dispute) and the ability to control a “de-centralized” “Greater Upper Nile”—location of the most lucrative oil production—with Riek Machar as puppet “governor. There is considerable discussion of the very substantial military assistance the regime intends to provide Riek.

The quotes are sufficiently numerous and explicit that I offer relatively little in the way of analysis or supplementary materials; but seen collectively, these statements make clear that war between the South and the Khartoum regime is increasingly likely. At the very least, the regime is helping to prolong a civil war that has produced near-famine conditions in South Sudan and has given rebel leaders Riek Machar and Taban Deng reason to believe that they might prevail militarily or enter negotiations in a much stronger negotiating position by virtue of military strength on the ground.

Willingness to commit substantial military resources:

Khartoum seems to have found common ground with Riek Machar:

“We must change the balance of forces in South Sudan. Riak, Taban and Dhieu Mathok came and requested support in the areas of training in [Military Intelligence], and especially in Tanks and artillery. They requested armament also. They want to be given advanced weapons. Our reply was that we have no objection, provided that we agree on a common objective. Then we train and supply with the required weapons. For sure we will benefit from their discourse. Taban apologized for the support he rendered to Darfurian movements and the role he played in Hijliij battle. That Dinka used them in that battle to spoil their relation with the North. But they discovered the mistake of late.” (1st Lt. Gen. Hashim Abdalla Mohammed, Chief of Joint General Staff, page 16)

The general continues by speaking about what amounts to the secession of “Greater Upper Nile” under cover of “federalism.” Of course, this is precisely the region where the most productive oil sites lie presently. Khartoum, as I warned last January, sees as a distinct possibility the de factoannexation of Upper Nile in partnership with Riek and forces loyal to him (certainly not all those in military opposition or the “SPLA-in Opposition”). In short, Riek sees this as an opportunity to create a lucrative fiefdom in the oil regions:

“Now they [Riek and Taban] are fighting to achieve a federal system or self-rule for each region. I think any self-rule for Greater Upper Nile is good for us in terms of border security, oil resources, and trade. Now we have to study how to enable them [on?] a well-trained force with efficient [Military Intelligence] and logistic staff.” (1st Lt. Gen. Hashim Abdalla Mohammed, Chief of Joint General Staff, page 16)

Of course Riek is not fighting for the principle of federalism, or indeed any principle at all: he is a ruthless, power-hungry man indifferent to the suffering that a prolonged civil war will bring. And certainly if he is supplied by Khartoum with logistics, tanks, artillery, and advanced weapons, he will be in a position to fight on indefinitely. General Hashim Abadalla Mohammed declares that “we have no objection,” stipulating only that “we agree on a common objective.” The oil of Upper Nile is that “common objective.”

Defense Minister Abdel Rahim Mohamed Hussein certainly shares this view:

“The people of South Sudan must accept to meet us and tell us their opinion on the drawing of the zero line and the buffer zone [This is simply a bald lie: it has been Khartoum that has for years resisted all efforts to resolve the North/South border disputes, short of total concession by the South. One must wonder if lying is so habitual in some men that it becomes for them the “truth”—ER]. If they refuse, we can deal with them in a manner that suits the threat they pose to us. I met Riak, Dhieu and Taban and they are regretting the decision to separate the South and we decided to return his house to him. He requested us to assist him and that he, has shortage in the [Military Intelligence] personnel, operations command, and tank technicians. We must use the many cards we have against the South in order to give them unforgettable lesson” (page 22 – 23). [Yet again use of the “card” metaphor, a reflection of Khartoum’s constant calculation of the “odds,” and when a gamble should be taken. Given the economic implosion in Sudan, the gamble of the moment in the oil regions seems increasingly attractive—ER]

Hussein’s is a thinly disguised and completely unjustified basis for military seizure of contested regions, with “Greater Upper Nile” nominally governed by Riek thrown into the deal.

Hussein’s “reasoning” has the support of Lt. General (PSC) Imadadiin Adawi, Chief of Joint Operations:

“Riak and Taban during their visit to Khartoum disclosed to us everything about the logistical support from Juba to the rebels, the route of supply and who transport it to them. Also gave us information about the meetings held between Juba and the rebels in regards to the disengagement between the two divisions and the SPLM/A South.” (page 14)

But there has never been strong evidence of substantial support from Juba for the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North. Small Arms Surveyhas found only limited evidence of assistance, and nothing that could seriously assist the war effort; indeed, SAS concludes that “the vast majority of the weapons documented with rebel groups originated in Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) stockpiles” (2014 Yearbook, page 20, Chapter 7). The two divisions of the SPLA-N—in South Kordofan and Blue Nile—were largely self-equipped when the breakup of the so-called Joint Integrated Units occurred prior to Southern independence. And particularly in the Nuba, General Abdel Aziz el-Hilu of the SPLA-N has seized tremendous quantities of weapons and ammunition from Khartoum’s Sudan Armed Forces and militia allies. Moreover, desperately embattled as it is, Juba is simply in no position, logistically or otherwise, to assist the SPLA-N. This is more angry fantasy presented as deliberation.

But guided by the same instincts, Lt. General Siddiig Aamir, Director of Military Intelligence and Security, is willing to surreptitiously invade South Sudan:

“The South is still supporting the rebels with the aim to change our government in Khartoum. In order to counter that danger, we are pre-empting them by a plan to infiltrate and empty the refugee camps [in Unity State and Blue Nile State—ER], recruit field commanders, and train the sons of the war affected areas to fight and defeat the rebellion [by the SPLA-N—ER]” (page 11).

What is clear throughout is that Khartoum sees no reason not to support the rebel groups in the South:

“[Juba is] still supporting the two divisions of Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile [This is simply not true in any significant sense now, if it ever was—more self-reinforcing mendacity within the regime, used as a means of explaining the crushing military defeats suffered earlier in the Nuba—ER]. Accordingly, we must provide Riak forces with big support in order to wage the war against Juba and clean the whole of Greater Upper Nile area.” Lt. General (PSC) Imadadiin Adawi, Chief of Joint Operations (page 14). [The verb “clean” here has extremely ominous implications, given the history of the regime’s engaging in what many—on many occasions—have called “ethnic cleansing”—ER]

There could hardly be a more explicit declaration of strategic ambition. That is will entail military conflict likely costing hundreds of thousands of civilian lives seems not even to occur even as a passing thought to these men.

In his summary comments and recommendations, recorded at the end of the minutes, Vice President and First Lt. General Bakri Hassan Salehmakes several terse but revealing comments:

“The greatest security and social threat is coming from South Sudan (foreign existence Uganda, America, France and Israel), the Armed Movements, South Sudanese and two areas displaced and refugees due to war (diseases, social crimes, children missing education and some converted to Christianity).” [The implicit equation of “diseases,” “social crimes,” with “conversion to Christianity” reveals a great deal about the way in which the National Congress Party/National Islamic Front regime thinks about the world—ER]

“We are not interested in any relation with South Sudan or the neighboring countries, but it is a reality that requires us to respond and deal with it.”

With such views, the Vice President “recommends” (these come sequentially):

These blunt recommendations, seen in the context of statements by SAF generals with most operational responsibility, augur renewed and expanded war in greater Sudan.

Abyei ablaze after Khartoum’s military seizure of the region, having previously denied the people of Abyei the guaranteed right to a self-determination referendum. Permanent annexation of Abyei will inevitably be one of the military ambitions if Khartoum sides with Riek Machar’s rebels in South Sudan.

Eric Reeves, 28 September 2014

MALAKAL, 16 June 2014 (IRIN) – Civilians displaced by brutal fighting in South Sudan are ignoring calls from government officials to return to their homes, preferring the safety of squalid UN bases to the risk that conflict could again engulf towns already devastated in the six-month conflict.

Amid a massive humanitarian operation, aid agencies had hoped that a cease-fire agreed in May would allow some populations to return and sow crops before the rainy season begins in earnest, thereby reducing the likelihood of a famine in the months to come.

But tension remains high, and interviews with internally displaced persons (IDPs) near the northern town of Malakal as well as in the capital, Juba, suggest slow-moving peace talks held in neighbouring Ethiopia must yield concrete results before civilians will consider returning home en masse.

“If a peace deal is signed, and the rebels really go back to where they came from, then maybe we can return to Malakal,” said Bongjak Chol, a 39-year-old warden for the South Sudan Wildlife Service. “But not before. I could be killed.”

Civilians abandoned Malakal and many other towns after a power struggle within the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) boiled over into vicious fighting that began in Juba in December and swept across the north and east of the country.

The conflict has split the army and pitted loyalists of President Salva Kiir against supporters of his former deputy, Riek Machar. Government troops as well as opposition fighters have been accused of massacring civilians on the basis of their ethnicity. Kiir is an ethnic Dinka, while Machar is a Nuer.

Thousands of people have been killed and an estimated 1.5 million driven from their homes, crippling government services and economic activity in much of the world’s youngest nation. Some four million people are in urgent need of humanitarian assistance.

While about 400,000 people have crossed into neighbouring countries Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda and Kenya, an estimated one million are displaced within South Sudan. That includes some 90,000 sheltering in the bases of the UN peacekeeping mission, UNMISS, which are now known as Protection of Civilian (PoC) sites.

Chol is one of 18,000 civilians squeezed into the PoC site in Malakal, where UN officials and relief organizations are striving to improve the dire living conditions.

Makeshift shelters made of sticks and plastic sheeting are packed together either side of a single main access road. Drainage is so poor that many of the shacks stand in water and mud that in places rises above the knee, even before the rains begin in earnest.

Children play along the road among garbage and razor wire, as trucks carrying earth from the site of a planned new camp edge past the tight rows of tea shops and food stalls. Flies buzz around dead dogs and cats, and smell of human waste is ever-present.

“Nobody can be happy here in the water and the dirt,” said Peter Gony, a 52-year-old ethnic Nuer community leader. “They are just waiting for the government and the opposition to make peace. But there is no peace.”

On the southern flank of the base, which lies a few miles (kilometres) north of the town, earthmovers were levelling a huge area to which most of the IDPs will be shifted in the coming months. IDPs have begun moving into scores of clean white tents erected on the first section. Relief organizations have built water points and latrines. Indian UN troops guard the perimeter, which is lined with earthen berms and razor wire.

Nyamet Nyibong, a grandmother who said she saw a nephew and a sister killed in the fighting, said the new facility was a big improvement.

“People were getting sick, sleeping on the wet ground. Here there is space, some wind and I can breathe,” she told IRIN, sitting on a low stool outside the new tent she shares with two sisters-in-law and other relatives. But she said she was frustrated by her forced inactivity.

“In the village we would be out planting sorghum and beans,” said Nyibong. “Here we just sit from morning until night, and we don’t know if this situation will improve.”

The difficulties at the base have persuaded some survivors to seek refuge elsewhere.

Across the nearby White Nile River, an estimated 60,000 people have descended upon the fishing hamlet of Wau Shilluk. Shanty-like settlements have spread along the banks of the broad river. A field behind has turned into a vast open defecation site.

Thomas Amun, a 33-year-old shopkeeper, said two of his relatives were shot for failing to hand over money and phones to opposition fighters who stormed Malakal in December. Amun and his family were among thousands who sought refuge at Malakal teaching hospital.

“Gunmen came looking for their enemies there. They were executing people at random,” he said.

When government troops re-took the town, which has changed hands repeatedly, Amun brought his family by boat to Wau Shilluk, rather than head for the PoC site. Friends loaned him a cow, and he sold its meat to raise the money to re-open his shop.

Amum said he was earning enough to keep his family fed. He was unsure he would ever return to Malakal. “I saw a lot of things there that were very bad for me. Until I can get it out of my mind, I don’t want to go back,” he told IRIN.

Malakal had been an important regional centre before the latest fighting broke out. The capital of Upper Nile State, it was home to many government offices. It was an important hub for traders bringing goods along the White Nile or from nearby Sudan.

When this reporter toured the town, the streets were largely deserted. A few small shops served tea and snacks to soldiers and a handful of civil servants ordered back to work. Some of those living at the UNMISS base were checking on their homes – or those of their neighbours – for anything that hadn’t already been looted. Many of the houses and shops had been burned to the ground.

The most visible human presence was a group of 26 families who had arrived three days earlier on foot and taken up residence in a ransacked mission school. In the school yard, children played among piles of scattered textbooks. The charred wrecks of five cars stood in an adjoining compound.

Peter Bol, a 34-year-old farmer, said rebels driven back from Malakal had been preying on his and neighbouring Dinka villages in Panyikang County.

If you don’t give them what they want, they threaten you,” he said. “There have been rapes and beatings.”

Having lost his stocks of maize and sorghum and his 30 cattle, Bol said he led the group to Malakal in hope of finding assistance. He said government troops advised them against going to the base because of the grim conditions there.

Still, UNMISS bases remain a magnet for scared civilians in a string of other towns, including Juba.

A semblance of normality has returned to the capital, where four-wheel drive vehicles clog the dusty streets. However, several residential districts remain emptied of their ethnic Nuer population. Thousands of the missing are crowded into a section of the UN compound beside the airport, while others have skipped the country. Many wealthier citizens of all ethnicities have evacuated their children to neighbouring countries.

In early June, this reporter watched as IDPs from the UN compound loaded suitcases and boxes bound with string onto two minibuses that would take them to Kakuma, a refugee camp just over the Kenyan border.

Mary Nyaluak, 48, said she already spent five years in Kakuma during the civil war in Sudan that ultimately led to the south gaining independence in 2011.

“I came to live in Juba because it was the capital of our new state,” Nyalauk said before boarding the bus. “Now I am going back to Kakuma because the government is against my tribe. They are killing us, even the children, and it is not safe to stay.”

She said 23 of her relatives had been killed in Juba in December, some of them beheaded. Surviving family members were already in Kakuma, she said.

International pressure for South Sudan’s leaders to end the war have been fronted by the regional grouping IGAD. Under its aegis, Kiir and Machar signed a ceasefire agreement on May 9, and promised “bold decisions” to bring peace and reconciliation, including the formation of an interim government of national unity.

However, fighting has continued in several locations and there has been little tangible political progress. It is unclear exactly when IGAD plans for the deployment of a regional Protection and Deterrent Force, mandated to protect IGAD military observers, will be realized.

“There has been a growing tendency to continue with the war,” Ethiopian Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn complained at a regional summit attended by Kiir and Machar in Addis Ababa on June 10.

Relief officials are not banking on any easing of the pressure on civilians any time soon.

“People are going to need to see much clearer signals that the fighting really is over and that there is reconciliation before they feel confident enough to start rebuilding their lives,” Toby Lanzer, the top UN humanitarian official for South Sudan, told IRIN. “I think we are still on a very downward trajectory.”

sg/am

http://www.irinnews.org/report/100223/fear-and-trauma-prevent-displaced-south-sudanese-from-returning-home

IN MALAKAL, SOUTH SUDAN BY TY MCCORMICK foreign@washpost.com This reporting was made possible in part by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Nyarony Choing is as old as South Sudan. And like the world’s newest nation, she has been to hell and back before her fourth birthday. When civil war broke out eight months ago in Juba, the capital, Nyarony’s mother fled with her three children, winding up in a refugee camp inside a base run by the United Nations in the northern city of Malakal. Every time it rains, which is often, the floor of their tent disappears under water, the thick, cloying mud of the Nile basin mixing with the human excrement that flows freely in the camp.

“The only thing worse than the conditions we are living in,” said Nyabac Chan Yor, Nyarony’s 26-year-old mother, “is the condition of my daughter.”

Less than four years after South Sudan declared independence from Sudan, a milestone that successive U.S. administrations worked to bring about, aid workers are racing to head off a large-scale humanitarian disaster. According to UNICEF and the World Food Program, close to a third of South Sudan’s population faces “acute” or “emergency” levels of hunger and malnutrition.

By the time Nyarony’s family made it to the U.N. base, the 3-year-old was emaciated and suffering from acute malnutrition. Her feet had swollen to

nearly twice their normal size — the result of water flooding into excess vascular space as her digestive system shut down — and her muscles had all but wasted away.

Nyarony is now gradually recovering after receiving medical treatment on the U.N. base, but thousands of children remain stranded in remote parts of the country, where they are at risk of starvation. Aid agencies estimate that 235,000 children could become dangerously malnourished by the end of the year, and 50,000 of them could die unless they get treatment.

South Sudan’s food crisis is almost entirely man-made. After eight months of civil war, about 1.1 million of its roughly 11 million people are internally displaced. Farmers missed this year’s planting season because of the violence. Livestock, which accounts for as much as 70 percent of the calories consumed by some communities, has been looted, killed and scattered in the mayhem. River trade, which forms a lifeline for many towns and cities cut off from the capital by road during the rainy season, has ground to a virtual standstill.

The humanitarian situation is “getting [more] desperate by the day,” Cosmos Chanda, the representative for the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, said in an interview from Juba. The fighting, he said, “has totally suffocated our ability to reach a lot of these locations” where people are at risk of starvation.

Experts have held off on making a formal famine declaration — there are specific criteria, including a death rate of 2 out of 10,000 people per day, which must be met before such a declaration can be made — but aid workers caution against waiting for that before taking action.

“The declaration of famine is a technical term. It’s a scientific thing that takes time,” said Jonathan Veitch, UNICEF’s representative in South Sudan. “It will be too late if we wait. We have to all act now.” Children are already dying, he said. By the time the United Nations declared a famine in Somalia in 2011, roughly half its 260,000 victims had perished, according to a study commissioned by the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization.

South Sudan also is facing a deadly cholera epidemic. Transmitted mainly through contaminated food or drinking water, cholera causes severe dehydration and can lead to death in a matter of hours.

“People are living in horrid conditions,” said Patrick Robitaille, the field coordinator in Malakal for the aid group Doctors Without Borders, “so disease is spreading very rapidly.” A total of 4,765 cholera cases were reported in South Sudan between April and the end of July, 109 of them fatal, according to the doctors group. But the outbreak could have been much more devastating; one of the small victories amid the conflict was an emergency cholera vaccination drive that has kept the disease from ravaging refugee camps.

Nonetheless, efforts to contain the outbreak — and to head off a potential famine — have been hampered by persistent insecurity in the country’s northeast, where most of the fighting has occurred. Despite an internationally mediated cease-fire, sporadic clashes between government and rebel troops have continued, and there have been reports of both sides obstructing aid to civilians. This month, six aid workers were targeted in what were apparently ethnically motivated killings.

The fighting began as a power struggle between President Salva Kiir and his former vice president, Riek Machar, but quickly took on an ethnic tinge. Kiir comes from South Sudan’s largest ethnic group, the Dinka, while Machar comes from its second-largest group, the Nuer.

More than 500 miles away in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa, peace talks have continued intermittently for months without making much headway. On Aug. 10, negotiators missed a key deadline to form a transitional government.

“Neither of the parties exhibit much urgency around the humanitarian issue,” said John Prendergast, a former Clinton administration official with years of human rights activism on Africa issues. He described the hunger crisis in South Sudan as a “ticking time bomb.”

If hostilities continue into the dry season, aid workers fear that conditions could deteriorate substantially. As bad as the situation is now, at least there are water and plants on which displaced populations can survive.

In Malakal, which has changed hands six times since the war began and where some of the worst atrocities have been committed, most of the refugees are living day to day.

“I just put one foot in front of the other,” said Nyabac, Nyarony’s mother, peering out of her tent at the rain slowly filling up the grimy tarpaulin world around her. “What else can I do?”

The Washington Post

25 Aug 2014

pg. A6

Meriam Yahia Ibrahim, a Christian woman from a Muslim background, was arrested on 17th February 2014 and charged on 4th March with adultery and apostasy. She is married to a Christian of South Sudanese origin. The couple have a young son (who is with Meriam in prison) and are expecting their second child later this month. The Government of Omar al Bshir (indicted by the International Criminal Court for Crimes against Humanity) does not recognise the couple’s marriage, hence the adultery charge.

Heavily pregnant and in a Sudanese prison – sentenced to 100 lashes and execution by hanging. Heavily pregnant and in a Sudanese prison – sentenced to 100 lashes and execution by hanging.

A further court hearing was held today (15th May). Meriam had been given three days to recant. However, at today’s hearing she calmly confirmed to the judge that she remains a Christian. The judge accordingly confirmed the sentence for apostasy of death by hanging. He also sentenced her to 100 lashes for adultery. The death sentence is to be imposed two years after she gives birth to their second child.

The lawyer acting for Meriam is preparing an appeal which must be submitted within 15 days. Meriam’s husband was not permitted to attend the court hearing today, and has been denied access to Meriam and their son in the prison.

Representations may be made to Sudan’s Misiter of Justice, Mohamed Bushara Dousa at moj@moj.gov.sd

The telephone number of the Sudan Embassy in London is 0207 839 8080

info@sudan-embassy.co.uk or tweet the UK embassy in Khartoum @SudanUnit